One of the greatest gains of the gay liberation movement and the general liberation movements around sexuality and gender was the possibility of rethinking all kinds of questions of affective relationships so that among gay men for example, if you stop thinking about finding Mr. Right, finding a lover or finding a marriage partner, and rather think about possibly sexualizing friendship, maintaining friendly relations with people whom you have had a romantic relationship or having fuck buddies, then a whole proliferation of ways of connecting with others opens up.

Douglas Crimp

Download interview in PDF format ![]()

An Interview with Douglas Crimp

February 14, 2011

Douglas Crimp’s Apartment, New York City

Douglas Crimp: My name is Douglas Crimp, we are in New York City, in my apartment in Lower Manhattan. I have been working as an art critic since 1970.

I took a big swerve in my career as editor of a cultural journal called October when during the AIDS crisis I decided to do a special issue on the subject of AIDS. This propelled me into the AIDS activist movement. I became deeply involved with Act Up (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) for about four or five years. During a longer period of seven or eight years, I pretty much exclusively wrote, lectured, and taught courses about AIDS. I was particularly involved with questions of representation of the AIDS crisis at the moment of the rise of what came to be known as queer theory in the American Academy. My work on AIDS was considered as contributing very much to that discourse and so as I was working on AIDS, I was also working on other questions of queer sexuality.

Carlos Motta: The AIDS issue for October was an unlikely topic for that magazine to approach. Can you explain how this issue came to be?

DC: October was an interdisciplinary cultural journal; it was not only an art journal. It has become much more rigidly an art journal subsequent to my leaving. For a long period of time October introduced post-structuralism theory to Marxist cores, but it was a journal interested in politics and a wide range of cultural issues. In 1987 when I did the issue on AIDS, I suppose I was moving more toward my own interests and work in what I eventually realized was the discourse of cultural studies rather than modern art criticism.

My intention was simple. I was interested in the fact that there was an art world response to AIDS. There were many people in the art world that became ill and died from AIDS. I was interested in the notion that you could use the monetary value of art to raise money for AIDS, whereas I thought that a political subject like AIDS could actually be taken on by culture as a subject. That was my initial interest in doing something in the journal. I didn’t intend to do a special issue, I intended to commission a few essays and thought I would write something myself, but realized I wasn’t knowledgeable enough. Talking to someone who became a friend, Gregg Bordowitz, who was a young AIDS activist making video work on AIDS, he said, if you want to know about AIDS, go to the Act Up meetings, and I did. Within a few weeks I completely changed my idea of what I had to do.

Book version of the original October issue.

Cover of AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism by

Douglas Crimp, published by MIT, 1996

CM: What happened at those meetings?

DC: I became very quickly educated about the extent of the crisis and about how people were responding to it in New York City. I realized this was an issue that deserved way more than a couple of essays so I immediately thought of expanding to do a special issue.

I asked my fellow editors of October and they said fine, go ahead. It grew from there, becoming very different from anything else in October because it was not a high theory approach to the subject but a mixed approach to writing about AIDS. For example, Leo Bersani’s famous essay “Is the Rectum a Grave?” was published alongside people who had no academic credentials, who were activists working in the movement, such as a prostitute who was doing activist work around prostitutes and AIDS. It became completely different from other issues of the journal and it made a real splash at the time, partly because it was so unexpected but also because of its hybrid form between the intellectual theorizing expected from October and this other range of artistic and activist voices.

CM: Your essay in that issue, “How to Have Promiscuity in an Epidemic,” is very interesting because it introduced a conversation that had been absent in terms of the representation of gay sex and its mediation by anti-HIV/AIDS campaigns. Can you share the argument you set forth and how you were grappling with the representation of gay sex at the moment?

DC: It wasn’t entirely original to me. There was a raging debate within queer communities at that time, really between what we might call the pro-sex activists and the more conservative voices that were saying gay people should basically stop having sex or stop having sex with too many people, as if somehow having sex with only one person, if you happen to be already infected, was going to make a difference. It was something I had been thinking about in terms of my own practice, my own life and in reading the press and following debates about, for example, the closure of the bathhouses and literature on AIDS that then existed.

Take for example two books addressed in that issue of October: Simon Watney’s Policing Desire and Randy Shilts’s And the Band Played On. Simon Watney would be a pro-sex position and Randy Shilts an anti-sex position. That is too simplistic but, reading Shilts, which was one of the books I was critical of in my essay, I was very struck by the return to clichés of homophobic discourse and wanted to show the way in which gay people themselves had fallen back on a discourse that labeled gay people as, for example, immature and irresponsible, within attempts to do something about AIDS.

My interest wasn’t to try to think about how you could maintain a healthy sexuality in relation to this epidemic through safe sex practices but how you could maintain a pro-sex positive position. How you could think about promiscuity and what we had learned from the wide-ranging experiences of having sex with many different people for many different purposes: For pure pleasure, for discovering things about yourself that you didn’t already know through an encounter with another, etc. How you could actually understand that as having given us the tools to invent the safe sex discourse in the first place. How for example you could have a viable public sexual culture in terms of bars, bathhouses, and sex clubs and so forth that would also become venues for the transmission of knowledge about safe sex practices.

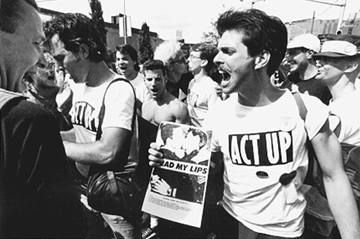

Archival image of an Act UP demonstration

Source: observatory.designobserver.com/entry.html?entry=20958

CM: Bathhouses and other places for public sexual encounters were the first places to be “cleaned up,” and it seems like the city was and has remained completely sanitized from that type of sites or venues. To your avail, did that representation of promiscuous gay sex ever change after the crisis? Or is that discourse still similarly based on morality?

DC: It is actually a fairly complex history that is multiply determined, things changed very drastically after AIDS, not only because of repressive forces. I think that the crisis itself, and people dying cast a long shadow over the pleasures of gay culture; not only were bathhouses and sex clubs closed by city ordinances in 1985, but also people just weren’t going out as much and taking as much pleasure in gay life, partly because they were afraid, but also people were busy fighting the situation or taking care of lovers and friends.

The explosion of a public sexual culture, which had happened between Stonewall and the early 1980s was really shut down. There was a combination of the repressive forces of government, the conservative voices among gay activists and then eventually a new kind of repressive regime in the era of Mayor Giuliani who was interested in shutting down night life generally in New York. It wasn’t only gay nightlife. He closed all kinds of clubs for the most minor violations like dancing near a jukebox if you didn’t have a cabaret license and that sort of thing.

I think maybe most important in all of this was that something of an enormous shift happened in the wave of AIDS toward a conservative gay culture where issues like fighting for equal rights to marriage and to fight in the military took precedence over what I think of as a truly queer culture, which is a culture that wants to change how we think about forms of human relations in a much more general sense. I still feel very much what I learned from early second wave feminism, which was the critique of marriage as an institution and how marriage actually served governance as a way of managing the complexity of relations that are possible among people.

One of the greatest gains of the gay liberation movement and the general liberation movements around sexuality and gender was the possibility of rethinking all kinds of questions of affective relationships so that among gay men for example, if you stop thinking about finding Mr. Right, finding a lover or finding a marriage partner, and rather think about possibly sexualizing friendship, maintaining friendly relations with people whom you have had a romantic relationship or having fuck buddies, then a whole proliferation of ways of connecting with others opens up.

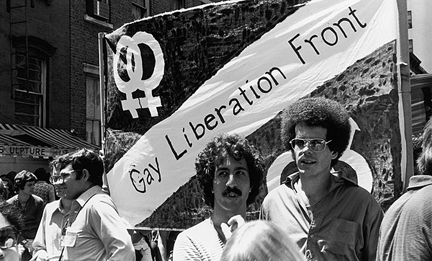

The New York chapter of the Gay Liberation Front in 1970. Photo by Fred W. McDarrah

Source: www.chicagoreader.com/chicago/hyde-park-university-of-chicago-gay-rights-stonewall/Content?oid=1490451

CM: In his recent memoir on his life in the 1970s, Edmund White writes about the “figure” of the lover merging into a singular figure during the AIDS crisis but before in the 70s he spoke about this figure as taking the shape of three different people: One he was affectionate with whom he had a romantic life and slept with, one he had sex with or fucked with, and one that was a friend. Does this merging of multiple figures into a singular figure work alongside your thoughts and writing at the time?

DC: I would even say that one could have many more than three figures. For example you could say there is one person you have vanilla sex with and another person you have S&M sex with. You could proliferate it in so many ways, but yes, that is exactly what marriage does. It becomes you and me against the world instead of a much more communal sense of sex and friendship. It is not simply about sex, although it is about an erotics of friendship, and sex is certainly central to it. I actually don’t think it is possible to get every kind of sex you could want out of one person.

CM: I have a sense that during the AIDS crisis and the closing of bathhouses and sex clubs something happened at an institutional level that became an unconscious collective turn toward the erasure of public sex and supported individualized subjectivity by understanding sex as something that cannot happen publicly or collectively. What do you think about this turn from a public to private sphere?

DC: The other thing that has to be thrown into the mix of course is the rise of the Internet in the 1990s, which completely changes sociality in a way I am incapable of theorizing. I participated in one kind of social sexual culture but I don’t participate as much in the new one.

I think one of the real differences is the public/private divide because what I miss in the present is the sociality of public sexual culture. I think there is an enormous difference between going online and being in a space where you see, talk and interact with an actual person, when you see the person’s subtle facial expressions, body language, etc. You only experience that in reality. You experience something else virtually. Public sexual culture however was extremely anonymous. Back rooms, for example, were often very dark. When I was using a back room culture, I would often see someone in the front of the bar where it was light and follow that person into the back room where it was dark and then have sex in that public space. Other people might join but my connection was to the fantasy image of the person whom I saw. Other people experienced it very differently, enjoying the pure anonymity of not even seeing the body to which an organ is attached or something, but public sexual culture actually made all of these variations possible. Different kinds of places had different degrees of lighting. Bathhouses, for example had dark rooms but also light areas or steam rooms that were not as dark.

Much of my experience of gay culture at a time when I was a nightly participant in it was about being in a public gay space that wasn’t necessarily a purely sexual space. A bar is not a purely sexual place at all, it is a convivial space, one where people laugh and talk, just look at each other, listen to the music or do all of these things at once. I think we have lost a lot of that. It is a little bit like the difference between going to the movies and watching a film on a big screen with a group of people whose reaction as an audience you participate in, and getting a film from Netflix and watching it by yourself or maybe with one other person.

Screen shot of bareback.com

CM: I am curious to know what you think about the rise of specific subcultures through online communities? For example, the bareback culture, a culture that has strongly emerged as an online community in the last ten years. BB sex parties are planned via the Internet and often prior to the party, it is pre-agreed that no one will use any form of protection and someone has already been designated as the bottom that will receive all of the tops’ sperm. The party is public and takes place in the physical, not virtual world, but private because of the way it is organized and cultivated online. What do you think about the emergence of that type of culture?

DC: I think the most interesting work that has been done on barebacking culture is Tim Dean’s book Unlimited Intimacy. Dean ends the book with a chapter called “The Ethics of Cruising,” in which he contrasts what happens online and what happens in urban and public space. He theorizes barebacking as a kind of radical openness to the other, which he sees, as I do, as one of the great positive forces of what I would call a truly democratic urban culture. With what you describe, I think it is true that one of the great achievements of the Internet is that you can find others who share your interests, in a way that would be rather difficult to do in just going to a bar. The most extreme example of this would be the case of the German cannibal who actually found somebody who wanted to be eaten. The likelihood of actually sliding up to somebody in a bar and saying: “I am a cannibal, I am interested in eating you, will you come home with me?” and finding a person who is willing to be eaten is highly unlikely. As a kind of organizational tool, take current Egyptian revolution as a current example, positive things can happen because of the Internet that could not have happened otherwise.

At the same time when you think about what Dean points out, something disturbs me about the Internet. Even the example of organizing this barebacking party, things are so controlled and prescribed in advance, it seems predicated on the notion that you know yourself, that you know your fantasy, and that you know your interests and desires. In a certain sense, then, you are not so radically open to the other. When I say the other I don’t mean only the interest or desire of another person that you have not been exposed to, but the other inside of yourself that you don’t yet know about. One of the great gifts for me of promiscuous, gay, sexual culture throughout the 1970s was that I discovered things I would never have known about my own sexual desire and pleasure because someone who attracted me in a bar led me toward possibilities of sexual pleasure that I wouldn’t have known. That is everything from people who are racially and culturally different to class different people and people who differed in their openness, age, and sexual interest. I mean a whole range of possibilities. When you go on the Internet as a bottom looking for a top with an eight-inch dick… How do you know that until you have opened yourself to exploration?

In the 1970s the ethos of gay liberation was that you should never cut yourself off from anything, like if you say you are just a top then you are denying the part of yourself that is a bottom or vice versa. If you say you are only interested in real men, you are denying a part of yourself that is interested in femininity. Of course that is a utopian rhetoric but there is a truth to it so far as that you don’t really know until you have tried it, maybe more than once even, or tried it in the right circumstances. This is also about a kind of denial of the unconscious; the notion that you could actually know yourself and know your desire.

Book cover of Melancholia and Moralism by Douglas Crimp.

CM: What is your perspective about the way AIDS is represented in contemporary culture as a manageable disease? I perceive a certain degree of amnesia amongst young people about the AIDS crisis and about the work that was done by Act Up and other organizations.

DC: Certainly, even for someone who was as involved in it as I was and as someone who deals with being HIV positive and takes the medications, it HIV/AIDS doesn’t have the same meaning as it did then. The epidemic is also different for many people than it is for me, such as people in this country and other countries who do not have access to drugs and health care. I think relative to younger generations in the United States there is no memory whatsoever, I mean there can’t be memory, they are born after all of this happened.

I remember when the presence of AIDS was in the newspaper every single day. In fact, I remember fighting to get it in the newspapers every single day when it was not being covered as much as we were experiencing it. I remember reading all kinds of articles on the subject daily and I also remember reading obituaries of people who had died of AIDS every single day. For many years my writing tried to follow and engage these various materials. Now you can go for weeks at a time and never see an article about AIDS in the New York press.

Of course many young people today are aware of sexually transmitted diseases and that AIDS is the worst of them. I think for gay men this is probably more meaningful because there is a historical memory and a sense of becoming infected so I think there is a consciousness but it is not a conscious discussion. It is a consciousness that is very individualized; people have to cope with this on their own. Things are much better than they were when people were dying, but in the sense that it no longer is a fear that people share and can talk about and can deal with together, it is worse. The notion of a support group for people who are HIV positive was totally common. The first thing your doctor would instruct you to do when you got a diagnosis was to find a support group. They were often institutionally constituted but you could find among your own friends a group of people that you could meet with and talk about seroconverting, or about finding out your status or how you were coping with your drugs and all of that stuff. Do support groups even exist now? Of course they do, they must, but the sort of sense of a community dealing with a crisis at once is gone because it no longer feels like a crisis.

Book cover of AIDS Demographics by Douglas Crimp and Adam Rolston

CM: In a way it feels like a controlled epidemic. Do you think that having controlled the epidemic and having access to medicine has changed the idea that we have of disease, of our bodies and of our own mortality? For example, if we think about the emergence of barebacking culture and the self-conscious position it generates of wanting to acquire this disease?

DC: There is a big difference between a disease that will almost certainly kill you and one that will almost certainly not. Even when I seroconverted, the “cocktail” was just starting and I remember my doctor saying to me at one point that I would not likely die of AIDS.

The trouble is that the question of mortality is different when you are young. For example, when you first lose a parent, there is something about that loss in and of itself that disturbs one’s psyche terribly. But one of the aspects of that disturbance is that you are confronted with death, not just your parent’s death but also your own. The encounter with death in general is like that: It is always double. When you lose someone you also recognize your eventual death and as you grow older, mortality becomes more present in your life in many ways. It could be because of an extreme illness or many deaths in your life or because you begin to lose your youthful vitality and don’t have the energy you once had. There are many ways that mortality becomes something we absorb as an aspect of living. This was always a consideration when we talked about the problem of teaching young people about safe sex, as an aspect of youth is the feeling that you will live forever, you haven’t confronted mortality yet, you are invincible.

It is very abstract for a young person to say: “This disease means that I will have to see a doctor every three months as part of the standard care, and that I will have to take medications for the rest of my life, medications which have side effects, medications which mean I must be conscious everyday of taking them at a particular time and not taking them may mean developing a resistance that could become dangerous to me.” All of the things that have to do with managing a disease are not transparent. You don’t recognize the reality of managing a chronic disease until you have one. It may not be AIDS, it could be diabetes, it could be many things but the kind of drag it is to deal with managing a disease is something that changes your life. I think young people who expose themselves whether deliberately or not to risk are not really fully conscious sometimes. Maybe some of the people in barebacking culture are conscious, maybe they have friends who know what it takes to manage the disease.

I myself don’t know what to think of a culture that involves notions of wanting to belong to the group of the infected, that sense of belonging that Tim Dean theorizes as a kind of historical kinship. It is a kind of metaphor that I am not sure what I think of, the notion of the virus as connecting you to all the other people who have transmitted the virus. I don’t actually know what drives barebacking and I think probably most of barebacking culture, and this is only just an assumption, takes place among people who are already infected. I think the people who are tops and the people who are bottoms may take for granted already having the virus and are not particularly worried about the so called “reinfection.”

CM: Why did you stop doing work about HIV/AIDS? Was it a natural fading out in terms of the timeframe of the crisis?

DC: It was multiply determined. Like many of the people I know that were involved in Act Up in fighting the AIDS crisis I felt burn out. You could only do it for a certain amount of time while coping with everything else. It may have had to do with my own seroconversion as it happened somewhat simultaneously. I felt I had done a body of work and that I also wanted to do and think about other things to give myself a break. Prior to the invention of the “cocktail” another thing happened, which was the gradual recognition over time within Act Up of the structural extent of the crisis of health care in the United States. We have seen recently, under Obama’s presidency, how utterly retractable health care is in this country. AIDS was mapped onto that, and we were no longer just thinking about dealing with the question of say, drugs into bodies, but also the incredible discrepancy between the way rich and poor people could access those drugs once they came through the pipeline. We began taking on a much bigger political issue, which felt insurmountable to some people. It became more consciously on all of our parts a huge global issue. To think about how you would make a practice of producing discourse about this became much more daunting. If that happens at the same time you are feeling emotionally burned out by the whole thing anyway, you just want to turn your back like myself and a lot of my friends did. I didn’t of course fully turn my back on it. I continued to teach about AIDS for a while. I continued to teach queer theory courses and my involvement with the AIDS crisis completely changed the nature of the work I went on to do. The work I am doing in my book on Warhol’s films is actually generated out of my interest in a kind of queer culture prior to gay culture, which after a period of liberation became the conservative gay culture we inhabit now.

Equality Rights March in Washington, October 2010

Photo by Jacquelin Martin AP.

Source: http://www.jacquelynmartin.com/blog

CM: It seems like the gay agenda today is very much set by three pillars: marriage equality, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and anti-hate crime legislation. When I think of this in relationship to the urgency the AIDS crisis brought I ask myself: Where is the sense of urgency within LGBTQ communities today? Where have we gone in terms of being involved, engaged, and politically active?

DC: I think there would people that would tell you gay marriage is an extremely urgent issue and for whom the activism around it is what they live for. I am not one of those people. Of course because of the conservative nature of these pillars, the people who are active are not activists in the way we think of the social movements of the 1960s and 1970s. I suppose they would go so far as to commit civil disobedience, but they are basically a very polite group of people. And they are often paid activists or lobbyists.

The question of political activism is a much bigger one and I don’t really have the answers to it. I don’t think activism ever fully dies, but rises in relation to circumstances. I think it goes back to what we were addressing before, which is the privatization of queer culture and the most vibrant and radical aspects probably of that culture are just less visible. There are radical sexual and cultural practices but they are more dispersed now and I think one doesn’t feel them in the same way. I see bits and pieces of radical queer scenes in New York. There is for example this group of young activists around the piers in the West Village that are organized and I see pockets of really interesting queer culture being made in the art world. Emily Roydson, for example, did a homage to David Wojnarowicz, where she reclaims, as a woman, at least the memory, if not the actuality of the queer sex piers.

Emily Roysdon, The Piers Untitled # 2, 2010

Source: http://www.emilyroysdon.com/index.php?/projects/the-piers-untitled

CM: What work are you currently developing around your experiences in the 1970s?

DC: My current work partially grows out of my experience in Act Up. I was about 20 years older than most of the people in the organization so I experienced gay liberation culture and the development of public gay sexual culture in the 70s. Most people in Act Up lived only the very tale end of that decade. Many people would say that I should write about the 1970s because we all felt the memory of that culture was being lost with the generation of people who were dying. I feel this very acutely today still. I have a friend who is just my age, Henry Abelove who is a very important figure in gay and lesbian studies in the Academy. He is working on the history of gay liberation because he feels that it is really lost, that what liberation really meant has become replaced by a simple notion of the Stonewall Riots as if liberation weren’t a much more complex history than that.

On another level I have pretty good stories about my life when I was first in New York in the 1970s, not just about my queer life, but about my art world life, which friends also encouraged me to write. As this was percolating, I taught a course at my university on Yvonne Rainer, the choreographer. Rainer was writing her memoir at this time and she showed it to me to help me prepare for the course. It is a beautiful memoir and somehow the fact that my friend Yvonne wrote her memoir made it possible for me to really think more about a memoir project. Not a memoir exactly as such because it is not my autobiography. It is about this forgotten New York in the 1970s but organized around anecdotes from my own experiences that create its genesis. It addresses precisely the question of this conservative gay culture that we inhabit today and the desire to reclaim a queerer and more vibrant sexual culture.

I could say the book is fundamentally about these two worlds I inhabited in the 1970s, the world of post-Stonewall gay liberation and the development of a queer sexual culture and the art world at one of its most experimental moments and how those two simultaneous aspects of my life often were in conflict as I experienced them. You could simply say that the art world is homophobic, and the queer world is philistine or something like that, but that is too polarizing. At the same time, I am interested in using that moment to speak about issues that are important in the present for me, in terms of the art and queer discourses. This is a way of using the past, as I think history always does, to inform the present.

CM: A productive nostalgia of sorts?

DC: I try to not have it be nostalgic. In some ways of course it is inevitable that it is because I was young and now I am not, but I think so far as it can be productive then it is not only nostalgic.

CM: How do you think we can reclaim a queerer life today? Everything seems so normalized, cleaned up, and conservative, with everybody working independently. Has that sense of collective utopia that you experienced gotten lost somehow?

DC: It is not for me to say how you can reclaim it or how young people will. Because of my age I don’t participate in contemporary queer culture in the same way that I participate in contemporary art culture. The question of sexual culture tends to be different as you get older. I can’t stay up really late at night very easily, I just get tired. I have a much more regularized relationship to when I go to bed and when I wake up and that is just a question of being 66 years old.

But we could also ask how to reclaim that moment when performance art was invented and people were able to use the vacant lots of Tribeca, as Joan Jonas did to make her great performance, Delay Delay in 1972. How can a young artist ever have the opportunity to have that relationship to the city or to art making? I think I can see it happening in other parts of the city and in varying art practices, I can actually see the excitement, the communal interest and the production of really extraordinary work that is comparable to what I experienced in the 1970s yet very different because of the different historical moment.

Radical Faeries parading in 2009, Atlanta, photo by N-Sai

Source: www.flickr.com/photos/nsaidi/4066339884

CM: A freer and queerer sexual culture is also happening today, although it is really just pockets of people here and there: From the Radical Faeries’ gatherings to different communal collectives in the city.

DC: Yes, but one of the great pleasures of the queer sexual culture in the 1970s in New York City for me was the sense of it being everywhere. You couldn’t take a subway ride without cruising someone, and when you went to one of the many discos thousands of people were dancing into the morning. Now, I ask my friends where they go dancing and I am shocked to learn there are not places to go dancing. I went dancing almost every night of the week in the 70s. I can’t imagine youth without dancing.

CM: How does the work you have been doing on Warhol relate to your work on the forgotten New York of the 1970s?

DC: They are actually related in genesis because even before I began working on a memoir proper, I began working on Warhol. I came to New York in 1967 and by 1969 I had moved to a loft in Chelsea and began going to the back room in Max’s Kansas City. By the time I was going there, Warhol had been shot but the scene was still there and I met a lot of the superstars from Warhol’s films and people from The Factory and the Theater of the Ridiculous. I began to think about this notion of a kind of queer culture prior to the establishment of the gay identity. New York in the 1960s was a kind of archeology of the scene I felt made me the queer that I am.

Initially I didn’t think about Warhol exclusively, I thought of doing something like New York queer culture in the 1960s that would include the Theater of the Ridiculous, the underground film making scene and artists like Jack Smith. I am not a historian, I am an art historian by training and I wanted to work on art, on objects and on artifacts. I wanted to interpret existing artifacts to write this so it would obviously be about culture. I started with an essay on Warhol’s Blow Job, which is a film I loved and was interested in writing about. Doing that I realized very quickly that I might as well stick to Warhol, there was more than enough material and I found the films so interesting and the writing on them was not that great at that point. I basically shifted my topic to Andy Warhol’s films. I taught courses on Warhol and began doing a lot of research and it developed from there. But it was really motivated by the notion of making available a kind of queer culture that I think has a lot to teach us about how we could be queer in the present beyond the kind of conservative identity-based, rights-based, normative gay culture of today.

CM: Can you explain more about the possibilities for making the queer culture your referencing available to the present?

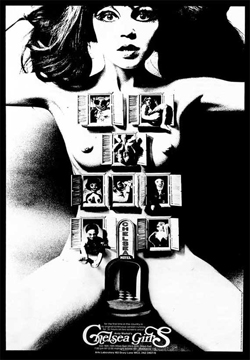

Andy Warhol, Chelsea Girls film poster

DC: It is a complicated subject, it is taking me a book to explain it! For example, I have a chapter on Chelsea Girls, which is a canonical and probably the most important Warhol film, but there is not great literature on it. My essay is called Misfitting Together. The title is taken from a Warhol quotation where he says people presumed that people from The Factory all thought alike but were in fact just a group of Misfits misfitting together. I used this idea to think the double screen projection in Chelsea Girls. Actually Yvonne Rainer wrote a review of the film when it came out and she talked about how watching Chelsea Girls is about watching the line between the two frames. I take this as a kind of deconstruction of the notion of the couple, or the idea that “two become one” because in Warhol two does not become one: It is a resistance to the notion of coupling. I am describing it very schematically and formally, but this switching plays out in the analysis of the film in terms of reading the reviews of it. There is an extraordinary review that was published in The New York Times that sees Chelsea Girls, I think rightly, as a kind of model of polymorphous conspiracy. It is really positive. It was written by a woman who basically is railing against the notion of films only being about heterosexual coupling and argues this film as the antithesis of that, because it is not about coupling and it is not about heterosexuality, it is about polymorphous possibilities. It is an amazing thing to think that in 1966 when the film came out someone in The New York Times, “Arts and Leisure” section could be writing positively about the film in those terms. It is about that kind of reclamation of accessing that notion of queer which pre-existed what we think of it. I mean we think of that as the time of abject sadness among gay people, as prior to their liberation, but of course it was a much richer scene than that.

CM: You have personally rejected coupledom too, right? You have chosen to remain single?

DC: Yes, it fits me much better. I could never limit myself to one person. What I reject is not so much coupledom itself, what I reject is the notion that one of the many important relationships in my life should take precedence over all the others. I really believe that I get different things from different relationships at different times and I don’t like the notion that one of them gets called the significant relationship. For me they are all significant in different ways and their signification changes from time to time. I am not going to settle and say this one matters more than this one. We used to have a term in the 1970s, “couples oppression” and it was really about how you were made to feel distinctly insignificant in comparison to the way the person in the couple treated the other person in the couple. You couldn’t have a relationship with one person in a couple without having imposed upon you a relationship with the other person of the couple. There were all kinds of ways you were diminished by somebody else's coupling. There were also people of course who formed couples, and I have many married friends today who are in relatively conventional marriages who nevertheless make a point not to inflict that notion of the couple on you so that you feel your relationship is significant, perhaps not equal, but not diminished by the so-called primary relationship.

↑Top